The SpaceX Grasshopper

Founder of PayPal, Chairman at SolarCity, and CEO and founder of SpaceX and Tesla Motors – there is no doubt that Elon Musk has some pretty impressive credentials behind his name. A billionaire philanthropist and inventor whose ambition seems to know no bounds, Musk’s innovation and charisma have served as powerful tools in building a worldwide fandom of people who see him as the man who will forge the bridge between present and future. PayPal to this day remains the only widely known company of its kind, despite its success. Tesla Motors is years, possibly even decades, ahead of their nearest competitors, and SpaceX’s Mars mission is just the start of what Musk envisages as an 80,000 person permanent colony. If you are unfamiliar with Musk’s exploits, you will probably be reading this with some scepticism, and rightfully so. The near impossibility of these projects certainly attracts cynicism, and it is so unlike modern day CEOs to show such vision and determination in their work that Musk can appear insane. But Musk’s success speaks for itself. Tesla Motors is now officially considered a threat in the auto industry, despite producing only electric vehicles, and SpaceX’s Grasshopper test earlier this year successfully landed a 10 storey rocket vertically, a first for the space industry and a phenomenal leap forward. I tell you this so that you may read about Musk’s latest invention with excitement and awe, rather than the cynicism and indifference that would be appropriate had anyone other than Elon Musk made this announcement.

.jpg)

The Hyperloop

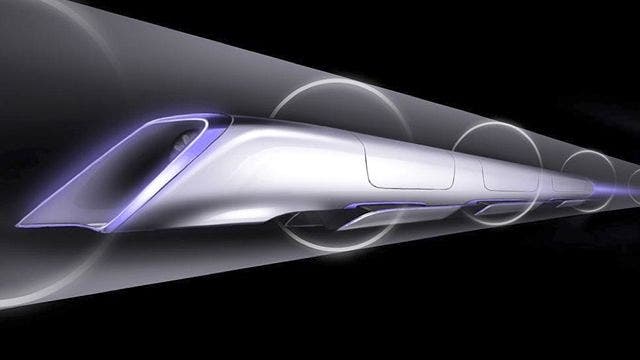

It is called the ‘hyperloop’. It is what Elon Musk sees as the ‘fifth mode of transport, aside from cars, trains, planes and boats’, designed to ‘fill a gap in the transport industry’. For short distances, such as around the inner city, the car is undoubtedly the most convenient way to travel. For slightly longer distances, between nearby cities such as London and Oxford for example, it is certainly quicker and more convenient to travel by train. For large intercontinental distances, the plane is the clear winner. But for the world of travel between nearby cities and transcontinental journeys, there is a gap. If you were to travel from London to Edinburgh, there is no convenient, comfortable, easy way to do it. A car journey would take far too long, a train journey is also painfully slow, and while the flight time from London to Edinburgh may only be one hour, travel time is at least doubled by the dull check-in and security process. There is currently no way to traverse these distances which does not produce a sigh of contempt when thought about. This is the problem that Elon Musk set out to solve, and the hyperloop is his answer. It is essentially a tubular transport system capable of travelling at transonic speeds at a very low cost, which sounds too good to be true, until you remember who thought of it.

How It Works

When people discuss ‘tube transport’, they normally mean one of two things. Either they are referring to something like the pneumatic tubes used to deliver packages around buildings, or they talk about magnetically levitated carriages suspended in a near vacuum. The problem with the first option is that for the 300 miles of tube needed to span from London to Edinburgh, the system would have to shift a 300 mile long column of air, which is incredibly inefficient. The second option would incur sky high costs in maintaining such a large volume of vacuum, and one small leak would bring the entire system down within minutes. The hyperloop is a mixture of the two: the pressure inside is low enough for it to be virtually frictionless, but it is also high enough for any leaks to be easily overcome by commercially available pumps.

The Hyperloop will ‘ski’ along the tube

When moving a capsule through a tube, the ratio of the cross sectional area of tube to pod has a role in determining how the capsule will travel; this is known as the Kantrowitz limit. If there isn’t much space for the air to escape around the edges of the capsule, the air pressure in front will increase and this will slow you down, which isn’t something you want to happen in a low-friction super-fast transport system. The hyperloop overcomes this by having a compressor fan mounted to the nose to distribute air from the front of the capsule down below the capsule and out the back. By doing this, it becomes far more efficient to run at supersonic velocities.

Magnetic levitation is very costly to maintain within a 300 mile long tube, and at such high speeds wheels don’t work very well. But the compressor fan used to overcome the Kantrowitz limit also diverts air to below a pair of skis mounted to the bottom of the capsule. This creates a cushion of air between capsule and the tube which can then be used to keep the capsule floating in a virtually frictionless environment for the majority of the travel duration, just like an air hockey table. Since the pod is creating its own suspension system simply by moving quickly, this also means the tubes containing the pods can be made incredibly simply, since they have pretty much no technicalities associated with them.

The Linear Induction Motor

So cruising at high speeds is sorted, but at low speeds, whilst the capsule is accelerating or decelerating out of or into a stop, the compressor fan can’t create enough of a pressure difference to lift the weight of the capsule. Yet at low speeds planes also can’t create enough of a pressure difference to lift their weight, and they overcome this problem with deployable wheels to accelerate to take-off velocity. So why can’t the hyperloop have deployable wheels to accelerate to the point where the cushion of air below the skis can support its weight? This provides a low friction method of suspending the capsule throughout the entire duration of the journey.

The next problem to overcome is propulsion. How do you accelerate a large object to the cruising speed of 760mph? The proposal is to use a linear induction motor, which uses electric currents to create an acceleratory magnetic field on the capsule. They work similarly to the spinning wheels you may have used to accelerate toy cars around tracks as a child: a track is mounted to the inside of the tube and creates the magnetic field, and a runner is mounted to the capsules and passed through the track. The magnetic field then causes this to accelerate, and the capsule continues to accelerate until it reaches the end of the track. With the virtually frictionless environment, the capsule then only requires a boost in speed every 70 miles.

Energy Requirements

The hyperloop was designed as an environmentally friendly, efficient way to travel. Musk’s proposed route from Los Angeles to San Francisco is estimated to require only 230 MJ of energy per passenger per journey; in comparison, the equivalent train journey is around 850MJ of energy per passenger per journey. So I think we can safely say this is a pretty efficient way to travel. The hyperloop tubes are also proposed to be built with solar panels running along the outer walls, and Musk estimates that on the West Coast of the United States, these solar panels will on average generate 57MW of power. He also estimates that the hyperloop will consume an average of 21MW, so not only is it completely self-sufficient, but it also generates an additional 36MW of power. While an equivalent system from London to Edinburgh would not generate anything like 57MW of solar power, it should at least be capable of generating its own energy requirement, which is a massive improvement on our current transport network.

The hyperloop was designed as an environmentally friendly, efficient way to travel. Musk’s proposed route from Los Angeles to San Francisco is estimated to require only 230 MJ of energy per passenger per journey; in comparison, the equivalent train journey is around 850MJ of energy per passenger per journey. So I think we can safely say this is a pretty efficient way to travel. The hyperloop tubes are also proposed to be built with solar panels running along the outer walls, and Musk estimates that on the West Coast of the United States, these solar panels will on average generate 57MW of power. He also estimates that the hyperloop will consume an average of 21MW, so not only is it completely self-sufficient, but it also generates an additional 36MW of power. While an equivalent system from London to Edinburgh would not generate anything like 57MW of solar power, it should at least be capable of generating its own energy requirement, which is a massive improvement on our current transport network.

Cost

The hyperloop has the potential to be 100% self-sufficient (and even generate excess power), completely green whilst running, and so much faster than any alternative. But surely it must be incredibly expensive? Well, the short answer is no. Musk’s estimate of the cost includes 50 capsules capable of carrying 28 passengers each or a considerable amount of cargo and the necessary earthquake protection for building the line across the San Andreas Fault. It comes to $7.5 billion, which is about £4.8 billion. The system could transport people, vehicles and freight between Los Angeles and San Francisco in 35 minutes, and by considering the cost of running the system and completely paying off the $7.5 billion initial cost within 20 years, would cost as little as $25-30 (£15-20) per passenger to run.

Conclusions

Personally, I am struggling to see the downsides of this project. I tried to find faults, but the engineering is more reliable than railways, requires far less maintenance and can even withstand an earthquake. It is cheaper to build than high speed rail networks by a factor of ten and the capsules need power for less than 10% of the journey. The hyperloop is the most environmentally friendly transport system ever created, harvesting more solar energy than it consumes, and it fills a massive gap in the transportation industry for medium-long transnational journeys. It would be easy to criticise the hyperloop for just being an A-B transport service, as it doesn’t stop at any major towns or cities along the way. But that would be like complaining that planes don’t land in the capital of every country they fly through – it isn’t what they’re designed to do in the first place.

The only other downside I could think of was that the project seems too ambitious; no-one will ever make it because it appears like an idea that is too good to be true, and so people will assume it is. This highlights the fact that the era of blind determination that took man from the edge of space to moon and back in under a decade has quite probably been confined to the history books. Elon Musk’s hyperloop represents the cry of a man who is sick and tired of our overly tentative advances into new fields of industry and engineering, calling out to leaders and businessmen to change the world.

Source:

http://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/hyperloop_alpha-20130812.pdf

![Elon Musk and The Hyperloop Founder of PayPal, Chairman at SolarCity, and CEO and founder of SpaceX and Tesla Motors – there is no doubt that Elon Musk has some […]](/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Blog-image-01_Bang-620x300.png)