Everybody knows about acne – it is estimated that 80% of the world’s population has suffered from it at some point in their lives. But have you ever wondered about the mechanisms that trigger acne? Why is it that some people are affected by it and others are not?

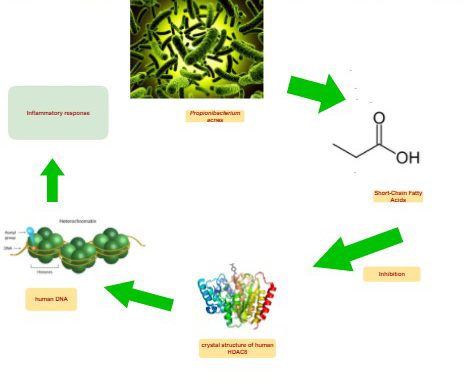

Researchers from UCS Davis have made an important step towards understanding this affliction, as shown in an article recently published in Science Immunology. In the recent study the team has found a previously unknown molecular mechanism through which a specific species of bacteria can cause inflammation in the skin. The research focused on Propionibacterium acne, a type of bacteria that has long been associated with the appearance of acne. Normally a harmless microorganism, P.acne can cause inflammation when in anaerobic (low oxygen), oily environments – a perfect description of the conditions found in hair follicles. In these circumstances, the bacteria produce substances known as short chain fatty acids (SCFA) from the sebum found on the skin. The study, led by Doctor Richard Gallo, showed that SCFAs cause inflammation through an epigenetic mechanism.

Epigenetics studies the genetic effects that are not encoded in the DNA sequence of an organism. Epigenetic changes do not alter the DNA sequence itself, but the way in which the genetic material is expressed by the organism

Thus, SCFAS inhibit 2 types of histone deacetylases, enzymes which affect the way in which the genetic material is packed and interpreted in the cell. Inhibition of these enzymes leads to the expression of genes that promote an inflammatory response. “Basically,” Gallo explains, “we’ve discovered a new way that bacteria trigger inflammation.”

This discovery could explain why some people are more susceptible to developing acne. They may have genes that make their skin more vulnerable to inflammation by these fatty acids or they have strains of bacteria on their skin that make excessive amounts of fatty acids. Teenagers are also more likely to develop acne- they produce more sebum which in turn leads to a higher production of fatty acids. Dr Gallo is also confident that these findings might lead to better acne treatments in the future: ‘’If we get lucky, it could lead to new medications in two to five years”.

This discovery could explain why some people are more susceptible to developing acne. They may have genes that make their skin more vulnerable to inflammation by these fatty acids or they have strains of bacteria on their skin that make excessive amounts of fatty acids. Teenagers are also more likely to develop acne- they produce more sebum which in turn leads to a higher production of fatty acids. Dr Gallo is also confident that these findings might lead to better acne treatments in the future: ‘’If we get lucky, it could lead to new medications in two to five years”.