I have raved elsewhere about the Wellcome Collection, the Wellcome Trust’s fascinating museum of medical equipment from throughout history. Forming part of the Collection is the Wellcome Library, containing manuscripts, paintings, journals, books and photos relevant to the history of medicine and science. Last week the library opened up their image archive to the public, and now anybody can freely use high-resolution images of these historical documents under a Creative Commons license. Here are some of my favourites.

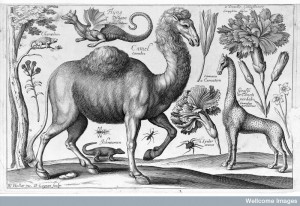

Hollar’s Exotic Animals

I love the images that Europeans made during the Middle Ages and Renaissance of exotic animals that they had clearly never seen with their own eyes. This particular illustration is by Wenceslaus Hollar, a 17th century etcher from Prague (who also spent some time on that historical ship, the Mary Rose). His somewhat sinister giraffe in particular betrays Hollar’s lack of experience with his subject, and seems to be most influenced by the Latin name for the animal – camelopardalis, or “camel marked like a leopard”.

Mattei’s Vials

These vials were owned the Italian count Cesare Mattei, who in the mid-19th century developed a system of treating disease which supposedly involved extracting a form of biological energy (which he termed “electricity”) from various plants. Different colours of this “electricity” would cure different diseases – for example, green electricity allegedly had an antibiotic effect. Sound bizarre? Then it’s probably not surprising that Mattei was influenced by Samuel Hahnemann, the founder of homeopathy – indeed his system was termed electrohomeopathy (and like that more familiar form of pseudoscience, still is practiced by some quacks today!)

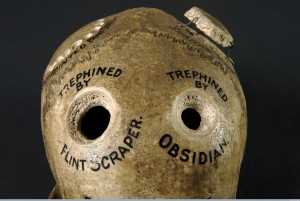

Cranial Trephine

If you go to the Wellcome Collection, you will see a large number of rather menacing medical devices. This one is a trephine, the tool used in a process caused trepanning, in which holes were bored into the skulls of patients with severe headaches, epilepsy or mental disorders. The practice began in ancient times, when it was thought to release evil spirits from the head, and still continues in some countries today. Modern practitioners believe that trepanning releases pressure in the skull, thereby allowing a better flow of blood to the brain – though there is little evidence that the process is beneficial, and it clearly carries huge risks (when neurosurgeons need to remove bits of skull to access the brain, they will usually replace them when they have finished!). This is what your skull would look like if you had undergone trepanning:

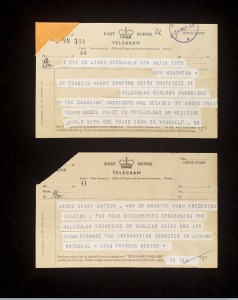

Francis Crick’s Nobel Prize Telegram

This is the telegram that Francis Crick received in 1962, notifying him that he had been jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his role in determining the structure of DNA. I just like the idea that one of the greatest scientists ever found out that he had won one of the most esteemed prizes in science for one of the most important discoveries of the 20th century in a slightly wonkily printed, single sentence telegram.

Science Art

Credit: Alexandr Khrapichev, University of Oxford, Wellcome Images. Licence

Alongside the “historic” section of Wellcome’s library, there are some more contemporary images. I picked out these two because they show how modern technology can be used to create some rather striking artwork. For the picture above, various fruits and vegetables were put in an MRI scanner, so that “slices” of these foods could be acquired without actually damaging them. The same principle lies behind MRI images of the brain or other parts of the body.

Credit: Spike Walker, Wellcome Images. Licence

This picture is an arrangement of fossilised diatoms, single-celled algae which are ubiquitous in light, wet environments around the globe. In fact, diatoms are so abundant that they are thought to be responsible for 20% of worldwide conversion of carbon dioxide into oxygen by photosynthesis – a role which could be harnessed to help combat global warming. They also look really cool under a microscope.

Want to see more? Go to http://wellcomeimages.org/ and have a browse through the image library. Feel free to share anything cool you find below!

![Images of Science I have raved elsewhere about the Wellcome Collection, the Wellcome Trust’s fascinating museum of medical equipment from throughout history. Forming part of the Collection is […]](/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/bang_blog_physiology-620x300.jpg)