Picture a heart attack. No doubt many of us will visualise a man clutching at his chest, struggling to catch his breath, his lips turning blue. However, often this image of the so-called “Hollywood heart attack” could not be further from the truth. 32,000 women die of heart attacks each year in the UK, and many experience none of these symptoms at all.

A heart attack, or myocardial infarction, occurs when the arteries supplying the heart muscle become blocked, depriving the muscles of blood so that they eventually die. In most cases this blockage is due to atherosclerosis, the process by which cholesterol and white blood cells accumulate in the artery wall. Although the dramatic “Hollywood heart attack” does occur, it is much more common in men than in women, who tend to experience more generalised symptoms, such as fatigue, vomiting and shortness of breath. These differences between the sexes in heart attack symptoms have long been noted but only recently has this area been explored empirically.

One study from 2012 looked at the over one million American men and women who had suffered from heart attacks within a twelve year period. The authors found that 42% of men presented with chest pain compared to just 30.7% of women, and that this symptom was even less likely to occur in younger women. Why such variation exists between the sexes is not known. One prominent theory is that higher levels of oestrogen may change the behaviour of blood vessels in women.

The current misconceptions surrounding heart attack symptoms are arguably fuelled by public health campaigns, which have historically failed to publicise these differences. Heart disease continues to be seen as a ‘male’ problem, with campaigns commonly using images of men and their symptoms. However, heart disease is actually the second biggest killer of women in the UK after dementia, and evidence suggests that women are less willing to get checked out when experiencing a suspected heart attack than men. Clearly, the bias in these campaigns needs to change if we are to encourage women to seek medical help for their symptoms.

Sadly, the prognosis for women who do seek help is still worse than for their male counterparts. One study, which looked at 10,000 patients with heart attack symptoms at emergency departments in the US found that women aged below 55 were seven times more likely to be misdiagnosed and sent home than their male counterparts. This troubling pattern of misdiagnosis of women has disastrous consequences: women sent home during a cardiac event have double the chance of dying than those that remain in hospital. Even the treatment of heart attack patients appears to be subject to biases between sexes.

Why do these major discrepancies in the diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of men and women with heart attacks continue to exist? One major reason is that up until this millennium almost all studies on heart disease focused on male participants. As a result, the medical community failed to realise that women experience distinct symptoms. Even now, women make up just 24% of participants in heart-related studies.

Nonetheless, change is on the horizon. In the US, the National Institutes of Health is investing 10 million dollars to include more women in clinical trials. In the UK, a recent study published in the BMJ found a new, more sensitive blood test could double the number of women diagnosed with heart attacks. Perhaps we are finally realising that heart attacks don’t discriminate – despite what Hollywood might have us believe.

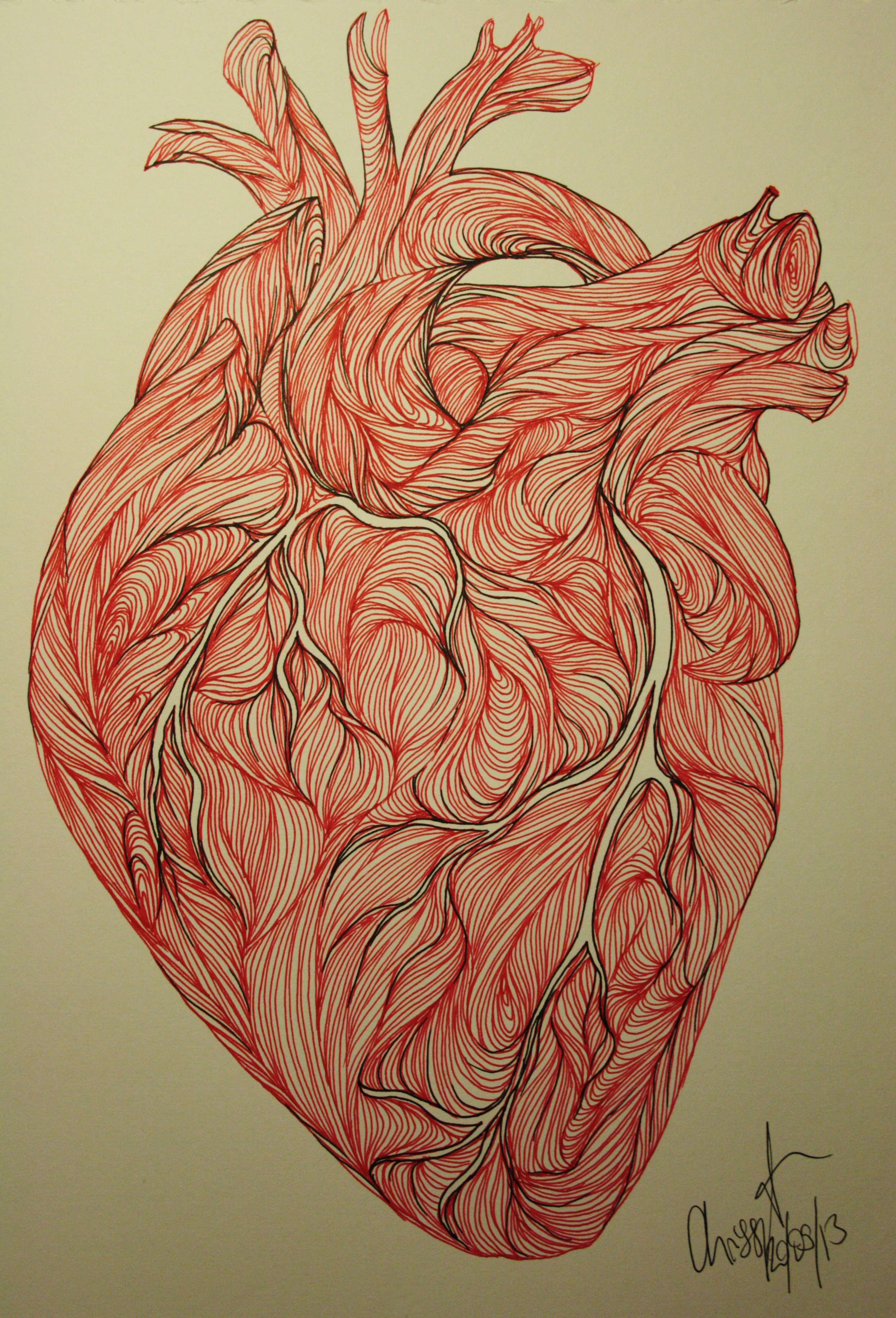

![The Heart of the Matter Natalia Cotton explains how differences between male and female heart attack symptoms are preventing women from receiving the best treatment. Picture a heart attack. No […]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/heart1-e1425205569703-640x361.jpg)